MOVIES I LOVE

Over the past decade, Paul Verhoeven's Elle has steadily ascended my personal pantheon of cinema, solidifying its place among my top ten greatest films of all time.

At first glance, Elle confronts the viewer with an unflinching depiction of trauma: a promiscuous woman is raped in the opening scene, her detached cat observing indifferently from the sidelines. Yet, as the film unfolds, it reveals itself as a profoundly layered exploration of agency, resilience, and the refusal to be defined by victimhood. The protagonist, Michèle, carries the weight of a harrowing childhood—her father, a notorious serial killer, burned his victims, and the tabloids framed her as a complicit figure in his crimes. Labeled a monster by society, she absorbs this condemnation and channels it, becoming the hardened, enigmatic woman the world seems to expect.

What makes Elle so extraordinary is its depiction of transformation. Over the course of the narrative, Michèle’s arc subtly dismantles the very identity imposed upon her. She begins to see through the moral binaries of victim and monster, breaking the generational cycle of violence that shaped her life. This is a story not just of survival but of transcendence—a meditation on redemption for those society has all but written off.

Verhoeven crafts a provocative, deeply human tale that dares to wrestle with complexity rather than settle for comforting conclusions. Elle is as much about confronting personal demons as it is about reclaiming power—and in the process, it becomes one of the most potent films about breaking free from the chains of inherited darkness. And did I mention it’s a Christmas movie!

In a previous review of The Blair Witch Project, I claimed that no other found-footage film could rival the one that started it all. That was before I saw The Taking of Deborah Logan. This film doesn’t just challenge that notion; it shatters it. It stands as one of the most terrifying films of all time, deserving a spot alongside the giants of the genre.

What I’ve always believed separates great horror from the rest is its ability to tap into something deeply primal. Whether it's Jaws exploiting our fear of being lower on the food chain, or The Exorcist provoking the unsettling thought, “What if everything in the Bible is real and there’s a cosmic battle between good and evil?”—these films dig into fears that are elemental, almost instinctual.

The Taking of Deborah Logan may, on the surface, be about an ancient possession, but at its core, it’s about something far more terrifying: Alzheimer’s. This disease runs in my family, and there’s no fear more primal than the slow, cruel erosion of memory. The horror of watching someone you love—someone who once looked at you with recognition and warmth—become a stranger.

This film helped me confront some deeply complex emotions surrounding Alzheimer’s, but it’s not an easy watch. For those who have lived through this particular torture, I’d offer a strong trigger warning—it brings to the surface fears that hit far too close to home.

As someone who has worked with emerging technology and writes horror films, I’m always grappling with the question: how can technology be truly terrifying? Often, I find that it isn’t, at least not in the primal sense that horror demands. Sure, there are films that have cracked the code—Pulse managed it, and certain episodes of Black Mirror effectively tap into modern anxieties. But for every success, there are countless misfires.

Influencer, however, comes surprisingly close to solving this dilemma. The film doesn’t just focus on technology as a tool but weaponizes it in a way that feels disturbingly plausible. The protagonist, marked by her unsettling birthmark, wields her technological prowess with such skill that it becomes the very source of fear. Her ability to take over people’s accounts, manipulate their identities, drain their bank accounts, and seamlessly move on to the next victim reflects a terrifying reality—one where existence is validated by nothing more than an Instagram update from a tropical beach. As long as you’re still posting, you’re still alive.

What makes Influencer stand out is how it uses this slick, modern thriller framework to explore a killer’s personal, envious motivations, all written on her face but never explicitly addressed in the plot. The film offers a glimpse into a near future where digital facades and curated lives are the norm, and with just a few keystrokes, anyone can become whoever they want—artist, writer, influencer, or even someone else entirely. It's a chilling reminder that the technology we casually use today could become the very thing that erases us tomorrow.

The brilliance and unsettling force that propels Tár is this: what if we framed a #MeToo narrative not from the perspective of the victim, but from the viewpoint of the person being canceled? This inversion is where the film’s true genius lies. It forces us inside the carefully constructed kingdom of Lydia Tár, a composer who has amassed power and influence, using it to devour admirers, elevate them to lovers, then discard them with impunity. She reigns supreme, able to crush the careers of anyone who dares challenge her or falls out of favor.

In this dominion, Tár wields her intellect like a weapon, effortlessly dismantling and belittling her students, treating them as mere pawns, lucky to even occupy the same space as her. Yet, as with all kingdoms ruled by fear, the subjects eventually revolt. Once Tár crosses the line by breaking her final protégé, her once-loyal subjects rise up, eager for blood, dragging her down from the heights of her prestigious career to the humiliating role of composer for Monster Hunter.

Todd Field’s film deftly exposes the mechanics of modern cancel culture—how even the most powerful can be toppled, though never completely destroyed. The real irony, and perhaps tragedy, is that in the capitalist circus, there is always a safety net. Even as Tár falls from grace, the system ensures she lands somewhere, though it may be as a diminished version of her former self—a clown in the circus she once ruled.

For years, I’ve wondered aloud, “Where’s the female Tarantino?” Sure, we’ve had great female directors, like Penny Marshall and Jane Campion, but where’s the director willing to go totally off the rails, unapologetically spilling blood and guts with the kind of chaotic glee that Tarantino brings to the table?

Well, Coralie Fargeat and Julia Ducournau seem to have heard the call. This movie is bonkers—so bonkers, in fact, that you could chop 20 minutes off the ending and people would still be buzzing about the carnage. Movies haven’t gone this full-on gonzo since Peter Jackson’s Dead Alive. The final act hits historic levels of gore, but some folks are missing the deeper cut.

A lot of reviews focus on the split between Sue and Elizabeth, as if they’re two completely different minds. Nope! The film’s point is way more interesting: it’s a metaphor for self-hatred—the younger you cringing at the older you, while the older you is embarrassed by your younger self.

Then there’s the scene where our protagonist processes the casting agent’s remark—Too bad she didn’t have those tits on her face'—and turns it into literal, Lynchian horror. It’s darkly hilarious but tragically spot-on. It shows how women are often shackled to what men think they should be.

Society of the Snow delves into the darkest, most unsettling chapter of the 1972 tragedy that befell the Uruguayan rugby team when their plane, Uruguayan Air Force Flight 571, crashed in the Andes. What sets this film apart is its deeply haunting twist—it is narrated by Numa Turcatti, a member of the ill-fated flight who did not survive. He isn’t just any narrator, though. He was a soccer player who had to learn how to pass the ball, a metaphor that quietly underscores the tragic, selfless role he would come to play in the survivors' journey.

As the film moves through the unbearable trials of the crash, the relentless avalanches, and the brutal cold of the Andes, Turcatti reveals that he was the last to die—his body, consumed by the remaining survivors, provided them with the literal fuel needed to make the grueling trek through the mountains, which ultimately led to their rescue. The narrative choice to have a dead man recount the story of his own death and his posthumous sacrifice creates a profound meditation on mortality, survival, and the staggering complexity of human endurance.

J.A. Bayona, no stranger to disaster cinema, masterfully reframes cannibalism—a horrifying act under normal circumstances—as a necessary and even poignant sacrifice. In his hands, the concept becomes less about the grotesque and more about the beauty of human resilience and the ultimate price of survival. The film is sad and emotionally wrenching, pushing its characters—and the audience—to confront the very limits of human morality and existence.

In Society of the Snow, Bayona crafts not just a survival story but a haunting reflection on sacrifice, elevating a harrowing historical event into something that forces us to rethink what it truly means to live, to die, and to endure.

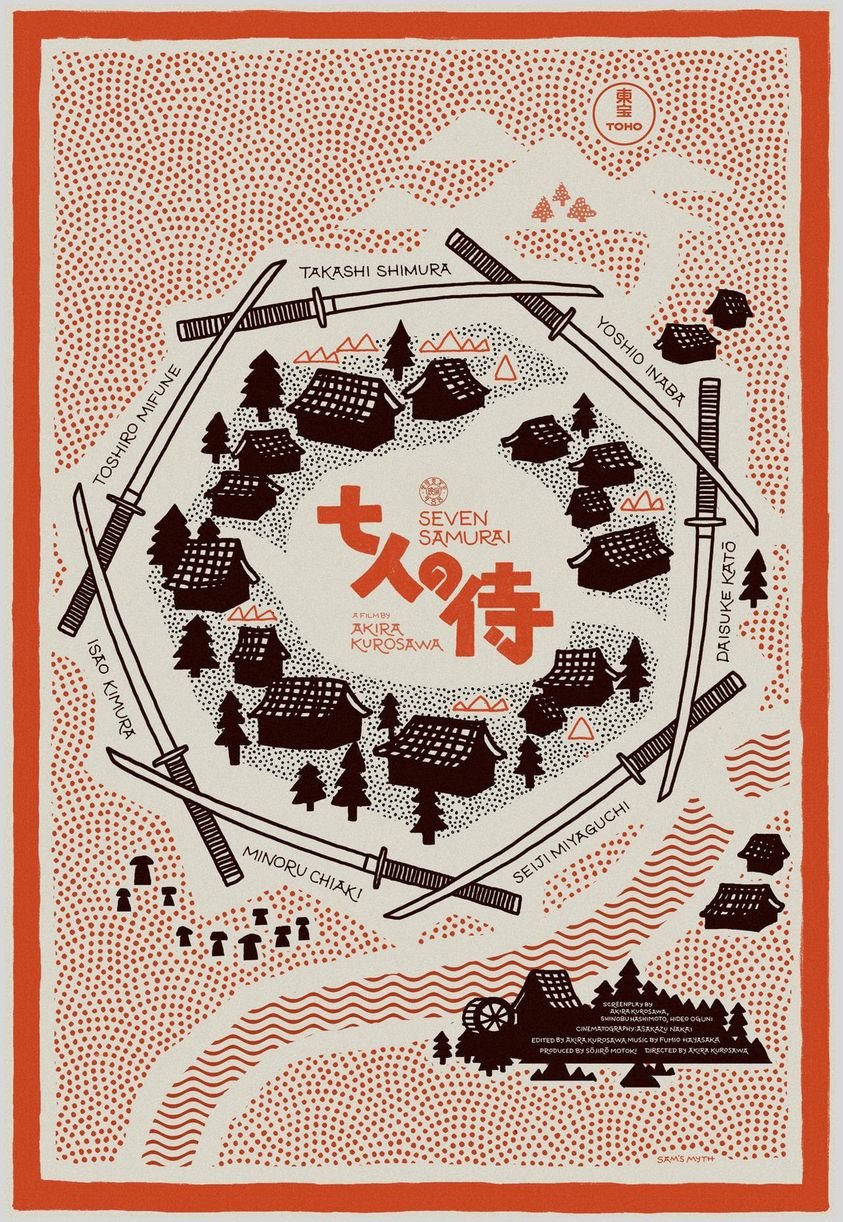

The Last Duel is Ridley Scott’s masterstroke in narrative complexity, echoing the structure of Kurosawa’s Rashomon by retelling the same events from three distinct perspectives. This ambitious approach poses a unique challenge: how does a filmmaker restart the story every thirty minutes without exhausting the audience? Scott rises to the occasion with remarkable finesse, using each retelling not merely to repeat events, but to subvert and recontextualize them, revealing the insidious nature of perception and memory.

The brilliance of The Last Duel lies in its ability to juxtapose seemingly identical scenes, only to unveil their true nature through the shifting gaze of its characters. Nowhere is this more apparent than in the pivotal sequence where Adam Driver’s character views a disturbing encounter as playful seduction, while Jodie Comer’s perspective forces the audience to confront the horrific reality of rape. This stark contrast between subjective perception and objective truth is the film’s razor-sharp commentary on the dangers of unchecked male ego.

At its core, The Last Duel is a searing indictment of masculinity, peeling back the layers of male rivalry to expose how men weaponize power not just to defeat their opponents, but to humiliate and emasculate them. Women, tragically, become collateral in these violent games of dominance, mere pawns in a contest they never asked to play. The script is riddled with uncomfortable questions about heroism, honor, and the self-serving myths men construct about their own nobility. As the film deftly reveals, these so-called heroes are often viewed not as protectors, but as foolish actors in an archaic charade. It’s a brutal exploration of power dynamics, where every "noble" act hides a selfish motive, and the victims, as always, bear the silent scars.

Guillermo Del Toro's Nightmare Alley spirals into a world of psychological and carnal madness, propelled by Bradley Cooper's magnetic performance. Cooper inhabits the role of a false prophet with chilling precision—a man who dares to mock the divine by perverting the gifts meant to uplift him. His character embodies a profoundly tragic figure, one who believes he's transcending moral boundaries but is instead inching closer to his own inevitable doom.

At its core, Nightmare Alley taps into the same existential undercurrents as Dostoevsky's Crime and Punishment. Both stories explore men who commit egregious wrongs and escape the literal consequences, only to find themselves trapped in an inescapable psychological purgatory. The true punishment is not the crime itself but the slow suffocation of guilt, a self-imposed mental prison that rivals any physical one. In Cooper's case, this prison feels as claustrophobic and degrading as the geek cage, a potent symbol of the dehumanizing spiral he can’t escape. The lines between freedom and confinement blur, and the deeper tragedy lies in the realization that his fall was never in the crime but in his own mind's unraveling.

Short Cuts is nothing short of a pioneering achievement, birthing a genre that paved the way for films like Magnolia and, unfortunately, Crash. Yet, Altman’s film stands as the true originator of this unofficial trilogy. It weaves an intricate tapestry of daily life in Los Angeles, where a sprawling ensemble cast moves through a city that feels perpetually on the verge of unraveling. Beneath the surface, as tectonic plates subtly shift, there’s a palpable sense that disaster is imminent, not just geologically but morally and emotionally.

Altman’s genius lies in his ability to strip away the layers of his characters, revealing the raw, unvarnished truths of their existence. By the time the inevitable earthquake strikes at the film’s conclusion, the tremor feels less like an isolated event and more like a seismic reflection of the internal ruptures that have been brewing throughout the story. It’s a portrait of a city not just on the brink of collapse, but of a civilization teetering on the edge of its own undoing.

Short Cuts doesn't just prefigure disaster—it prophesies it. And while Magnolia and Crash would go on to explore similar themes of a city damned, struggling with fractured human connections and redemption, Altman’s film remains the most visceral, the most prescient. His vision of Los Angeles is one of inevitable decay, where salvation feels out of reach, and yet, the inhabitants continue to grasp desperately at fleeting moments of meaning in the face of an impending apocalypse. Altman doesn’t merely predict the collapse; he captures the slow, steady disintegration of a world that can’t quite admit it’s already begun.

In its early slate of films, Pixar established itself as the premier storyteller of modern morality tales, seamlessly blending entertainment with profound life lessons. Toy Story dealt with the complexities of jealousy, Inside Out explored the nuances of our emotions, and Up captured the essence of eternal love. What sets Pixar apart, however, is its refusal to opt for simplistic resolutions. As the studio evolved, it began to infuse its films with deeply adult themes, posing questions that are often left untouched by children's cinema.

Finding Nemo marks a pivotal point in Pixar’s maturation, where the studio began confronting larger issues in earnest. On the surface, it’s a charming tale of an overprotective father searching for his lost son, but beneath this heartwarming narrative lies a much more adult concern—learning to let go. Marlin, the father, embodies an understandable yet crippling fear of loss, and the film poignantly explores how that fear can hinder both parent and child. It's a story just as much for adults as it is for children, reminding us of the inevitable challenges of releasing control and trusting the world.

In Finding Nemo, Pixar shows its mastery of tackling big ideas in deceptively simple packages. The film marked the beginning of the studio's deep dive into complex, existential questions—issues of fear, control, and acceptance—all wrapped in the bright, candy-coated visuals that make them palatable for audiences of all ages. It's not just a film about a lost fish; it's a meditation on the emotional journey of parenthood, one that lingers long after the credits roll.

The War of the World: The New Century is a dark satire that echoes the themes of Orwell’s 1984, centering on the control and manipulation of truth. The story follows a television anchor who, under coercion by invading Martians, becomes the mouthpiece for their propaganda. His role is not merely to report the news but to keep the population docile, suppressing panic while his wife is held hostage and he is violently punished for deviating from their script. This is not a film that relies on subtlety—it opts for a sledgehammer over a scalpel, carving out a biting critique of media control and coercion.

Much like 1984, the film explores the terrifying power of media as a control tool. The most chilling moment comes near the end when, with nothing left to lose, the anchor attempts to break free from the Martians' hold and deliver an authentic message of rebellion. However, his defiant speech is distorted during the broadcast, twisted into a message of compliance. Instead of inciting revolt, the altered broadcast urges people to remain docile. The news later reports that the Martians have left and everything is fine, but the insidious truth is clear—they are now embedded within the government. The TV is not just a medium of information but a device of mass pacification; to control it is to control society itself.

In many ways, the film embodies Malcolm X's famous warning: "If you're not careful, the newspapers will have you hating the people who are being oppressed and loving the people who are doing the oppressing." The War of the World: The New Century amplifies this message, underscoring the terrifying consequences of a reality shaped by manipulation and control, where the truth is constantly reshaped to suit the needs of those in power.

The Iron Claw deliberately sidesteps the prevalent question that dominated wrestling in the 1970s and 1980s: is it real? Unlike Darren Aronofsky’s The Wrestler, which focuses on the physical toll these athletes endure, The Iron Claw chooses a more measured and reflective path, delving into the emotional and psychological toll that wrestling exacts on a single family.

The film is straightforward, but a devastating emotional depth lies beneath its simplicity. It tells the story of a father who demands unrelenting discipline from his sons, pitting them against one another and dismissing vulnerability as weakness. This is the curse of the Von Erich brothers—a family trapped within the suffocating confines of their father’s expectations, a tragedy that ultimately claimed many of their lives.

The Iron Claw is a profoundly heartbreaking film. It doesn’t need to embellish its message—the raw tragedy of this family's story resonates powerfully on its own, making it an unforgettable exploration of familial pressure, loss, and the cost of impossible standards.

Triangle of Sadness is a masterful blend of the satirical bite of Luis Buñuel and the absurdity of Monty Python. The film owes a clear debt to Buñuel's The Exterminating Angel in its portrayal of the upper class gradually stripped of their luxuries until their hypocrisy is laid bare for all to see.

The narrative is elegantly structured into three distinct acts, each designed to explore the behavior of the privileged when they find themselves both at the pinnacle of society and at its most desperate nadir. One of the most compelling arcs involves a male model who initially condemns his girlfriend for expecting him to pay for their meals, only to find later himself prostituting his body for mere pretzel sticks when the social order collapses. Similarly, the cleaning woman who listens to "New Noise" by Refused offers a glimpse into her internal rebellion, a subtle yet profound hope for a world where the first shall be last, and the last shall be first—an aspiration she ultimately brings to fruition.

The Monty Python-esque absurdity emerges at the film's core, particularly in the prolonged, grotesque sequences of vomit and excrement. What begins as an over-the-top spectacle soon transcends distaste, becoming a bizarrely hypnotic display. We need works like this to shock us out of our complacency, forcing us to confront the absurdities of our world.

I've long believed that Christopher Nolan is, at his core, a structuralist. By this, I mean that he is primarily concerned with the architecture of his films—the way they would look if mapped out on a graph or chart. While this might sound overly academic, what sets Nolan apart is his ability to fuse this cerebral approach to filmmaking with genuine emotional depth.

Take Memento, his second film, as a prime example. The story is told in reverse, with a protagonist suffering from short-term memory loss. With each backward shift in time, the character, Leonard, must reorient himself—asking the fundamental questions of existence: Where am I? What brought me here? What am I doing? In the hands of a lesser director, this structural conceit might serve as a mere intellectual exercise, a clever trick with little more than surface-level appeal. However, Nolan transcends this by transforming Leonard’s forgetfulness into a profound commentary on the human condition.

As the film culminates—in what is, paradoxically, the first scene—we realize that Leonard has deliberately constructed a false narrative, setting himself on a path that, while misguided, gives his life meaning. He needs this purpose because, without it, he is nothing. And isn't that a reflection of all of us? Aren't we all pursuing some elusive goal, clinging to a sense of direction? The real question is—how many of us would even know what to do if we ever truly attained it?

You have to admire the unyielding conviction behind Blonde and how fully it embraces its darkness. Rather than just brushing against the edges of despair, this film dives headfirst into it, as if peering into the inside of a coffin. Blonde doesn’t just include one abortion, but two, along with a miscarriage—Andrew Dominik was adamant about making these moments pivotal to his grim vision. Even the seemingly lighthearted scenes on the set of Some Like it Hot are tinged with references to them.

I can understand why some might dislike this film. I haven’t always been a fan of Dominik’s previous work, which sometimes felt needlessly bleak and cynical, almost as if it were for show. But in Blonde, the darkness feels earned. Drawing inspiration from what David Lynch might have brought when he was once attached to Marilyn Monroe’s story, Dominik creates a chilling narrative about how the relentless search for maternal love can sow the seeds of our destruction. I’ve known many people who grew up without mothers or fathers, and it leaves a wound that never fully heals. The strongest among them find a way to turn that scar into a gift, transforming it into their superpower. But for many, that central wound—being abandoned when they were most vulnerable—is too deep to conquer. This is a story about someone who succumbed to that wound.

So many films ask us to accept moral relativism, meaning they serve to blur the line between what is good and what is evil. This is healthy, as it helps us understand all perspectives and makes us well-rounded viewers. Occasionally, though, it's nice to see a movie that does the exact opposite. FRAILTY views righteousness as black and white; it's a film that posits that the world is filled with evil people who do unspeakable things and good people who were put on this earth to hunt down and kill them.

One of the most unusual film screenings I've ever attended was seeing Terrance Mallick's THE TREE OF LIFE a year before it was released. When the lights came up, there were two types of people in the tiny screening room: weepy film students and baffled executives scratching their heads asking, "what the fuck do we do with this?"

This film can be overwhelming if you approach it with an open heart.

Orson Welles's response to being criticized for exaggerating his creative contributions to CITIZEN KANE in Pauline Kael's "Raising Kane" was to make a documentary about a famous art forger. F FOR FAKE is a playful take on authorship and Welles's own dubious relationship with the truth, his tendency towards exaggeration, and a proclivity for "printing the legend."

Dario Argento made some singular films, but he never really topped his first, which has an unforgettable murder staged in a bougie art gallery. Separated by the glass, our hero is forced to sit back and watch a poor helpless girl be skewered. THE BIRD WITH THE CRYSTAL PLUMAGE is a combination of high art and shlock, and unlike other Argento films, it at least has the semblance of making sense.

It's no small feat to create your own belief system on film, but that is just what DEFENDING YOUR LIFE does. The film shows an alternate version of purgatory where your life plays out like a trial where you must defend your life choices. It depicts planet earth as a spiritual school where humans are meant to learn lessons to grow to move forward to the next stage of existence. It's a strangely life-affirming film because it gives the viewer clear directions on how we are meant to conduct ourselves, and like religion, it offers hope for redemption if we make the right choices with our time here on earth.

It's an old motto that art is subjective, but Banksy seems to take issue with that in EXIT THROUGH THE GIFT SHOP. Here, he sends up a kind of populist art that is ironic but ultimately empty. The film draws a clear line between what is worthy and worthless, and it takes no prisoners as it mocks those who fall for Mr. Brainwash and his distinct brand of bullshit, including Madonna and Brad Pitt.

The documentary may be the best thing made about what it means to have honor and what it means to sell out.

SULLIVAN'S TRAVELS follows a movie director who purposely makes himself homeless for research on his upcoming picture. No scene hits harder than the one where Sullivan, now rendered penniless and detained, watches the delight as a bunch of prisoners light up at the sight of a Mickey Mouse cartoon. The film is a mission statement about the need for entertainment as an escape instead of making art that wallows in despair because it's considered "important."

As is often the case with movies that start a genre, the first instance is usually the best, and what follows pales in comparison. I mean, every shark film made following JAWS was living in the shadow of a cloud in the shape of that killer shark movie. Similarly, THE BLAIR WITCH PROJECT remains the best found-footage movie. This fear the film produces directly relates to the filmmakers trying to convince us that these events actually happened. This starts with the idea of sending actors into the woods and having producers and directors behind the scenes pulling the strings to generate tangible fear. It also spreads to the marketing, with websites that built up the lore and invited viewers to become detectives solving a mystery.

Once this film was released, the magic trick was performed, the rabbit was out of the hat, and there was no putting it back. Other found footage films came and went but never reached this height. BLAIR WITCH, like THE EXORCIST, serves as a reminder that making a film that terrifies people has everything to do with how seriously the filmmakers take the premise. If the people making the film are truly scared, that fear will translate to the audience.

In terms of provocative films, it doesn't get more morally queasy than THE NIGHT PORTER. The film is directed by a woman and remains one of the most transgressive films ever made. THE NIGHT PORTER focuses on a sadomasochistic relationship that develops between one of the guards and an inmate in a concentration camp. It's the kind of plot that would make even Jerry Lewis say, "isn't that a bit much."

I kind of love that Alan J. Pakula went straight from THE PARALLAX VIEW to ALL THE PRESIDENTS' MEN. The former may be the most over-the-top conspiracy film of all time, complete with cigar-chomping men in smokey backrooms working on brainwashing techniques to create sleeper agents. The film's message stops just short of declaring, "It's the Illuminati doing it!" And even then, it basically says that.

ALL THE PRESIDENTS' MEN couldn't be more different; it's a grounded film based on an actual conspiracy that had only occurred a few years earlier, the details of which had become extensively publicized. Watching both movies back-to-back offer two case studies on handling this type of political thriller: on polar opposite ends of the spectrum.

One of the few things Lars von Trier made that actually observes the rules of Dogme 95; THE KINGDOM is laugh-out-loud funny, with many sequences that suggest a blending of TWIN PEAKS and French farce. For pure entertainment factor alone, this is the most watchable thing Trier ever made.

Speaking as someone who has endured SALO, OR THE 120 DAYS OF SODOM, THE HUMAN CENTIPEDE, and A SERBIAN FILM, I still think the most disgusting thing ever put on film is Isabelle Huppert’s character having sex with a guy wearing his sweaty hockey gear on the bathroom floor in THE PIANO TEACHER.

The film is a character study that takes us into the dark subconscious of someone with sexual hang-ups so deep-rooted they would make Freud jump out a window.

It’s unfortunate how relevant Fellini’s LA STRADA still is; the push-pull dynamic it depicts between a macho man and the woman foolish enough to love him is a tale as old as time. The film can reduce people to tears because of what it says about the tragedy that plagues most relationships: put simply, that you don’t know what you’ve got till it’s gone.

I love this poster; the idea of a movie being advertised using famous composers is so anachronistic and charming. People forget how transfixing FANTASIA is; it's often neglected when people talk about Disney's many contributions to cinema. The Sorcerer's Apprentice remains the most iconic segment, but the portion set to Beethoven's Pastoral Symphony focusing on half-nude female centaurs is hilarious, and the Night at Bald Mountain segment is still frightening, painting a perfect picture of what the composition evokes.

James Cameron's title card at the end of TERMINATOR 2: JUDGEMENT DAY says, "Written, Directed and Produced by James Cameron." To put that in perspective, that means not only did Cameron write, "The T-1000 flies the helicopter underneath the overpass, its blades spinning mere feet beneath the concrete, its skids nearly touching the pavement," but he then had to convince a stunt pilot to do it. And to top it all off, he watched it all play out, biting his nails, knowing he would surely shoulder the blame if anything went wrong with the insane stunt.

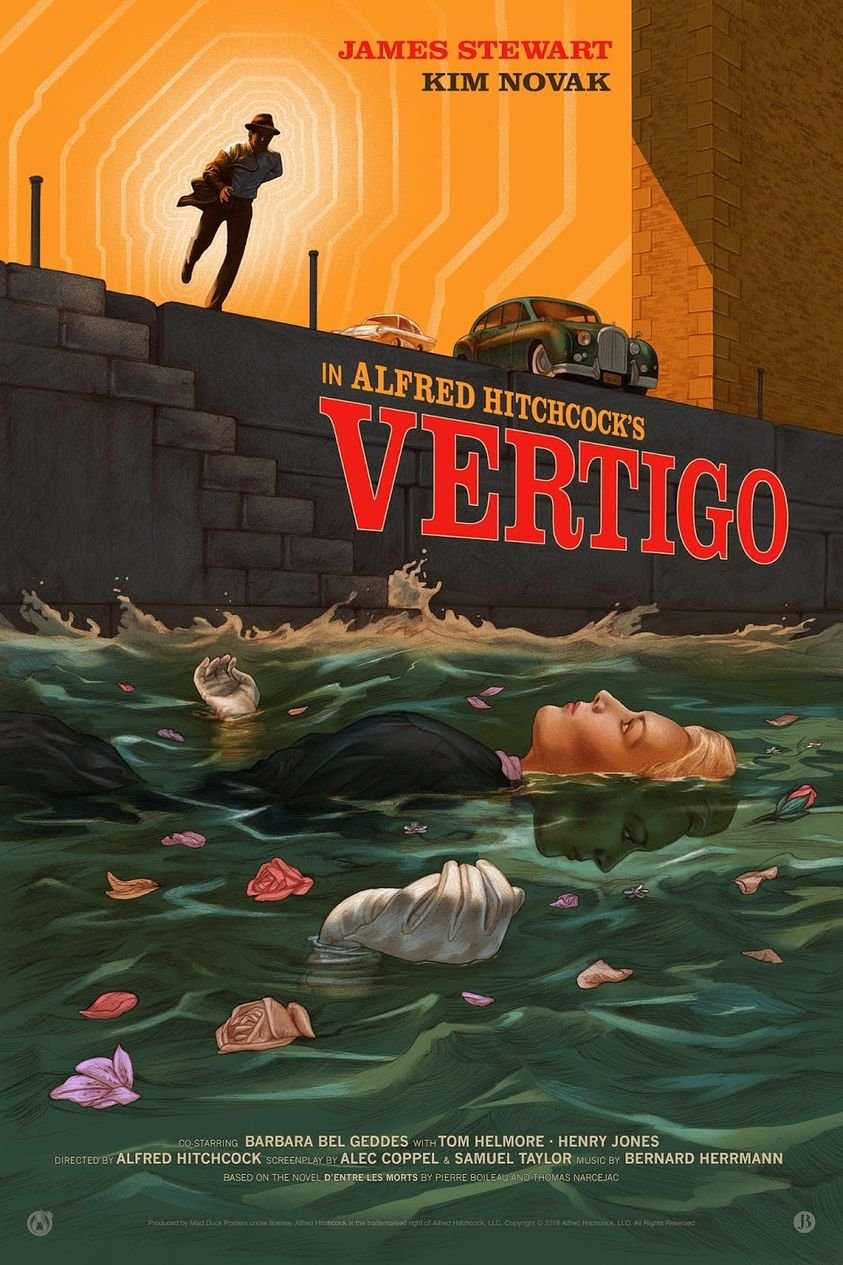

VERTIGO may be the first instance of auteur cinema. Dismissed as a middling film upon release, the movie only grew in esteem over the years, now routinely topping lists of the greatest films ever made. That it grew in people's view is directly correlated with rabid film fans dissecting it through the lens of Alfred Hitchcock, the man, the perfectionist who plays dress-up with blondes to recreate memories of a love long gone (or who never was.) For better or worse, the trend of reading films as portals into the subconscious of their visionaries started with VERTIGO.

THE AVIATOR didn't get enough credit for taking the road less traveled. Rather than ending on a down note, Scorsese makes the third act about Hughes's triumph over mental illness. You hear someone is making a Howard Hughes biopic, and you immediately think the third act will chronicle the downward spiral, Kleenex boxes, jars of piss and all.

Another thing I've grown to admire about the film over the years is how it depicts paranoia. Between this, TAXI DRIVER and SHUTTER ISLAND, Scorsese is the chief purveyor of paranoia on film. THE AVIATOR somehow manages to add another layer to his continued fascination with this subject. Yes, Hughes was paranoid, but the head of Pan Am Airways was conspiring against him behind the scenes. In the penultimate scene, when Hughes suspects his Spruce Goose victory party has been infiltrated by spies, he is right. The film questions the thin line between paranoia and awareness. If you are rich and famous, you inevitably end up with more rivals, and it's not paranoia if they're really after you.

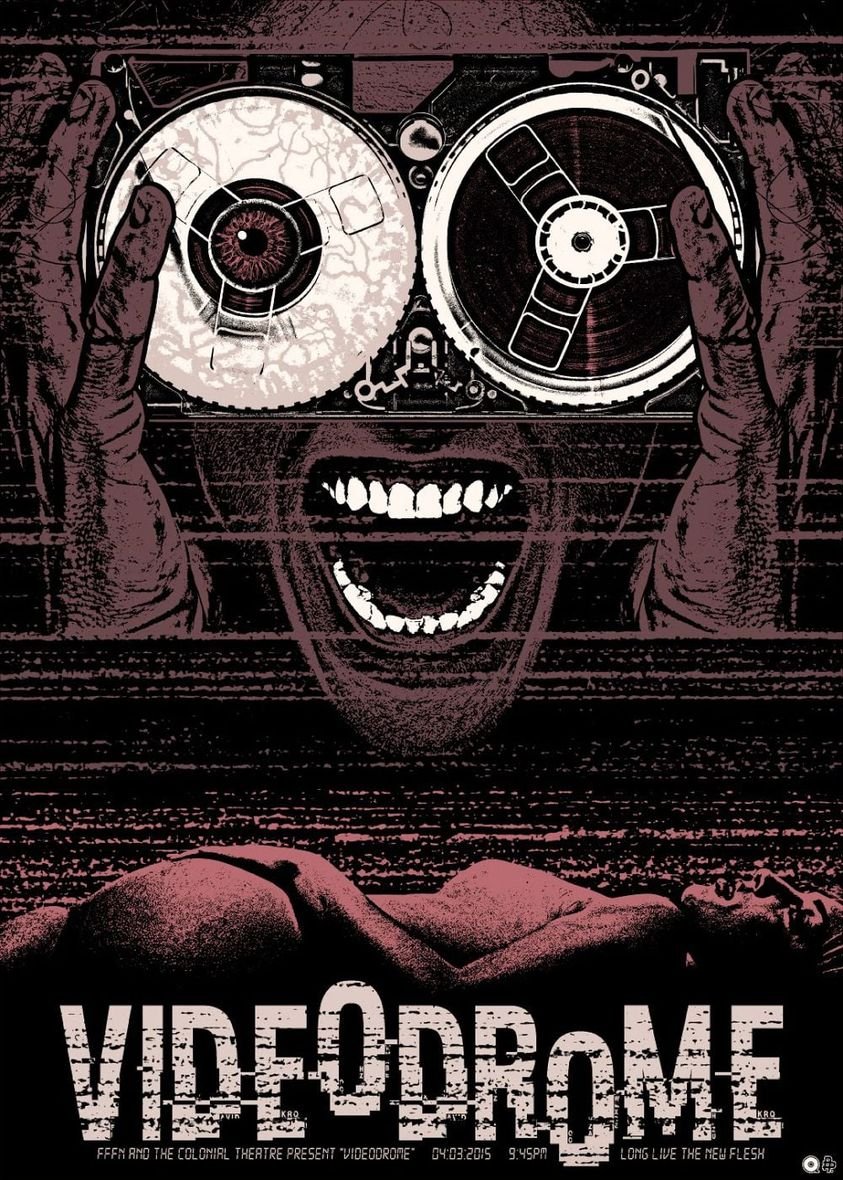

David Cronenberg leaned into the criticism leveled at him and Brian De Palma and John Carpenter in the early 1980s. Around this time, there was much hullabaloo made about how movies caused people to be violent. Rather than shy away from this critique, Cronenberg was inspired by it. VIDEODROME audaciously admits, "yes, media is making people more violent, and it's only going to get worse." The film is halfway between a satire and a confession, and the fact that you can never tell how much of it you're supposed to take seriously only makes it that much more seductive.

DEMOLITION MAN was made at the perfect time, snuck in before political correctness became a religion, the film envisions Los Angeles as a progressive nightmare. Since so much of what it's satirizing has come to pass, it almost plays better now.

Although BONNIE AND CLYDE is credited with starting the golden age of cinema in the '70s, it really started here, with Mike Nichols's debut film. Even after all these years, WHO'S AFRAID OF VIRGINIA WOLF? remains one of the best acted, shot, and blocked movies of all time. The film's acting style straddles a line between "play to the rafters" theatrical and the soon-to-be-popular Stella Adler method technique. The way people move in this film is still mesmerizing; it's an affront to the boring conventional blocking people had grown accustomed to up until this point. Here, actors finally feel alive in their environment.

Made three decades before the words "school" and "shooting" became all too comfortable beside one another, IF…. centers on a traditional British public school, it shows us its strict rules and regulations the students must endure, and then it asks us to celebrate as the teens take up arms against the headmasters. It's safe to say it's a movie that would never be made today.

A film that has just a satisfactory first and third act with a masterpiece sandwiched in the middle, COLD MOUNTAIN depicts the civil war like a portal to hell opened up and demons came spilling out all over the south. It's like a Hieronymus Bosh painting come to life.

STRAW DOGS is obsessed with powerlessness and emasculation. It doesn't really take place in the countryside in England; as much as it takes place in the mind of someone who fears outsiders, it borders on xenophobic in its depictions of the "other."

It's a film I've struggled with over the years, finding it at times maddening and enthralling in equal measure. What is fascinating is every move Dustin Hoffman's nebbish mathematician character takes in the third act. You'll notice he doesn't kill anyone until they have unlawfully entered his home or attacked his person. In that sense, the film's finale is the ultimate conservative revenge fantasy, as the preyed upon lone wolf can exact righteous death upon all those who come near his wife and his castle.

A film that shows how ostensibly trivial things can add up to a life-changing epiphany, 45 YEARS doesn't lead to one big blowout moment; it instead shows little moments that dig away at its female protagonist's psyche, as she slowly realizes her relationship is built on a lie. A terrifying reminder that anyone can fall out of love in a week, even after spending a lifetime together.

If you watch Oliver Stone's best film, TALK RADIO, it's hard to believe it isn't based on Howard Stern. It feels like an unofficial biopic (even though it isn't.) The film feels like it prophesied Stern, among other things. It's a flawed character study of someone cursed with a big mouth. A man who would rather talk his way to an early grave than censor himself.

For all the flaws Stone has as a director, his best movies are the ones where he aimed his discriminating eye at the media. In these films, he comes off as a soothsayer. It's hard to watch the end of TALK RAIDO, where various callers chime in with their feelings, and not see the parallels with the rise of YouTube, where everyone can be an asshole with an opinion.

The best word to describe WEST SIDE STORY is immaculate. The film is perfect, from the lighting to the cinematography to how the bodies move in precise rhythm. It really has more in common with animated movies like FANTASIA than with any other live-action film. That it feels this controlled goes to show you the amount of pressure put on these performers; it must have been a hell of a movie to make, either that or the film Gods were smiling down and blessing the production from up high.

Robert Altman made a Lynchian film before anyone knew what that word meant with 3 WOMEN. The film visualizes unspoken communication in the feminine sphere, a psychic bond, and a language that men cannot understand. Fittingly, it's an ethereal, nearly impenetrable film that feels as contemporary as something A24 would put out.

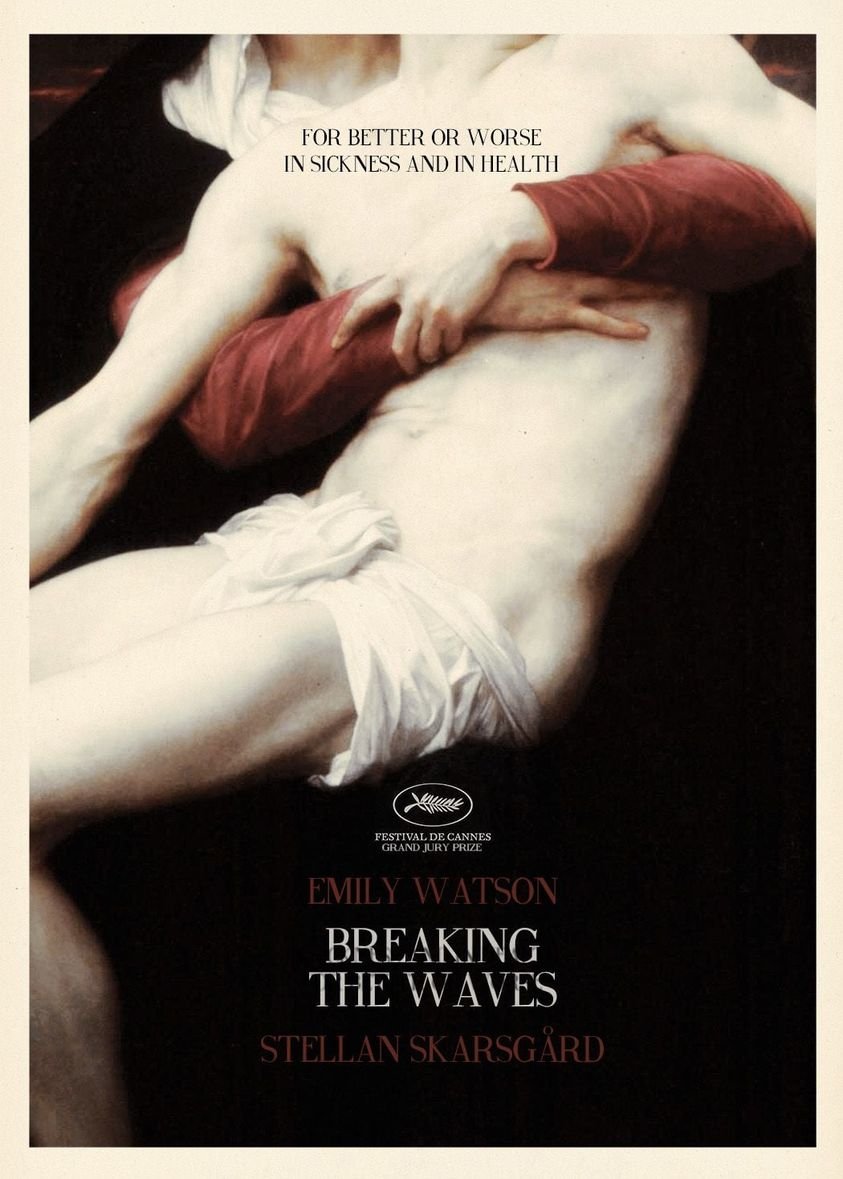

One of the most heartbreaking films of all time, BREAKING THE WAVES, finds a thoughtful criticism of blind faith in the form of a dutiful wife who takes her drugged-up husband's delirious orders at face value. It remains Lars Von Trier's best film, partly because it walks a perfect tightrope between melodrama and realism.

SICARIO has an opening that puts you on the edge of your seat, and the film doesn't ever let up. In fact, the only respite the film takes turns out to be a red herring, as our female protagonist takes home a male suitor, only to find out he too wants to kill her.

What lingers about SICARIO is that it's one of those rare Hollywood films about failure; it doesn't offer any solution to the complex issue of the drug cartels in Mexico. It's a funeral, mourning the ever-growing catastrophe happening right under our noses.

A genuinely heartbreaking movie that dramatizes a failure of communication. WALKABOUT is two movies at once; from the young woman's perspective, it's a film about how an Aboriginal boy helps her and her brother through the Australian outback. The Aboriginal boy sees it as a love story, but the young woman doesn't realize that he is courting her because they come from totally different cultures. An incredible film by Nicolas Roeg, who made a series of masterpieces all about subjective perspective.

AN OCCURRENCE AT OWL CREEK BRIDGE is a case study in raising the stakes. It begins with a character about to be executed. He is hunted like a rabid dog when he escapes. It may be the best short film of all time, and the way it pulls the carpet out from the under viewer has been imitated by countless feature films that bill themselves as having a twist.

A great fish out of water story and still an underseen film, Billy Wilder’s ONE, TWO, THREE sends a hard-nosed exec from the Coca-Cola company to Berlin to sell the communists on the popular beverage. He is also tasked with keeping an eye on the boss’s firebrand daughter, who moves to Berlin and promptly marries a communist. A zany, screwball comedy that is enhanced by characters rooted in the real world.

The best scene in THE GAME is seldom discussed. After Nicholas survives the "game" of the movie's title, where he suspected nefarious forces were trying to take his money and his life, he is approached by his brother Conrad and shown the bill to pay for the budget for the event. Based on Nicholas's reaction, it's a high price tag, but he has no problem paying it; after all, money seems trivial after what he's been through.

What is so funny about this moment is, if you think about the entire thing as a sting designed to get Nicholas's money, this is the moment where he willing hands it all over. The perfect swindle is one where the person being stolen from surrenders with a smile.

MAY is a campy horror film that doubles as a fascinating character study about a woman who seeks perfection in people but can't help but focus on their best parts. The film is riddled with exciting characters who grow to be hypocrites in May's scrutinous eyes, like an aspiring horror director who loves blood on-screen but winces at the sight of it in real life. The film feels like a retelling of Pygmalion or Frankenstein through the eyes of someone with Asperger's syndrome.

I think LOOPER is going to have the same legacy as BLADE RUNNER. Sci-fi similarities aside, I think both films were not fully understood upon release. In BLADE RUNNER, the notion of Deckard being a replicant was a hypothesis that grew over time, it was never the definitive interpretation of the film until people foisted this interpretation on the film, and then it became the most popular fan theory of all time.

Similarly, I think there are layers in LOOPER that went over people's heads when it was first released. Throughout the film, there are little hints that Cid, the child who will grow up to be the legendary Rainmaker, is also a variation of Joseph Gordon Levitt and Bruce Willis's characters. Watch the film with this interpretation in mind, it makes it even more moving, and I'm 89% sure it holds up to scrutiny.

Although I may have just been really, really high when I came up with this hypothesis. Either way, it's my story, and I'm sticking to it.

Not so much of a movie in the traditional sense. UNFAITHFULLY YOURS is instead a series of set pieces where a purportedly two-timed orchestra conductor pictures revenge fantasies centered on the killing of his seemingly adulterous wife. By the end of the film, the man realizes he was mistaken; his wife was loyal and pure, yet he was on the verge of butchering her! The film chalks it all up to the artist's temperament.

SPENCER is like THE COOK, THE THIEF, HIS WIFE & HER LOVER, but the Thief is the stodgy rules and regulations of Christmas holidays with the Royals. The comparisons don't end there; both films are obsessed with food and have a structure that follows the regiments of each day until the third act, where the monotony is broken, and our heroine finds her freedom.

Society has changed so much since the early '90s, where being a princess was perceived as the ultimate wish fulfillment. Flash forward thirty years later, and here's a film that shows us the most famous princess of our time, and it's basically a horror film. The beautiful costumes are laid out as sparkling traps designed to shackle the Princess of Wales' autonomy. No scene emotionally affected me more this year than the one where Diana's favorite dresser hands her a note that says something like, "I'm not the only one who loves you." As a film, it's also as weird as TWIN PEAKS, with a score by Jonny Greenwood that sounds like it was inspired by Angelo Badalamenti.

The most punk thing Alex Cox did when he went from his absurd debut REPO MAN to SID & NANCY was turning in an earnest drama. The film presents the punk subculture as a bunch of lost children who had too much fame too early. Mix it with a pair of star-crossed lovers, and it's a recipe for tragedy.

A story unveiling itself as fantasy taking place in a character's mind just before they die has become a bit of a cliché. Although when JACOB'S LADDER first came out, it hadn't been seen before, so you can't blame the film for being imitated. You can see the fingerprints of Adrian Lyne's LADDER on things from SILENT HILL to THE SIXTH SENSE, and it still packs a punch, with sequences that will forever live in the mind of anyone who has witnessed them. It's a hallucinatory fever dream dramatizing the feeling of clinging onto life in the face of overwhelming evidence that we must accept death.

Unfortunately, the definitive version of ALIEN 3 exists somewhere between the theatrical cut and the assembly cut. At the time of the film's release, people couldn't get past the casual killing of Hicks and Newt, but if you think about it from a different perspective, ALIEN 3 follows the tradition of ALIEN, in that Ripley is the sole survivor thrust into a new world to explore.

It's an uncompromising film that drags the franchise and its main character to a literal hell on earth and offers no solution to combating evil other than sacrificing yourself.

MARTYRS somehow manages to elevate the otherwise irredeemable genre of torture porn into something actually resembling high art. The key to its staying power is it finds a logical reason to skin people alive and take them to the brink of death that isn't some outlandish revenge plot. The reason they torture in MARTYRS is rooted in the spiritual world; it posits that by bringing someone to the verge of death, you may discover the meaning of life.

THE CHANGELING from 1980 is a film that has fallen by the wayside in the conversation of great horror films. Its most horrifying sequence involves a little girl who wakes up to find a kid submerged in water and trapped under the floorboards.

In the end, the film reveals itself to be a bit of a political thriller; THE CHANGELING feels like if Alan J. Pakula had made THE OMEN.

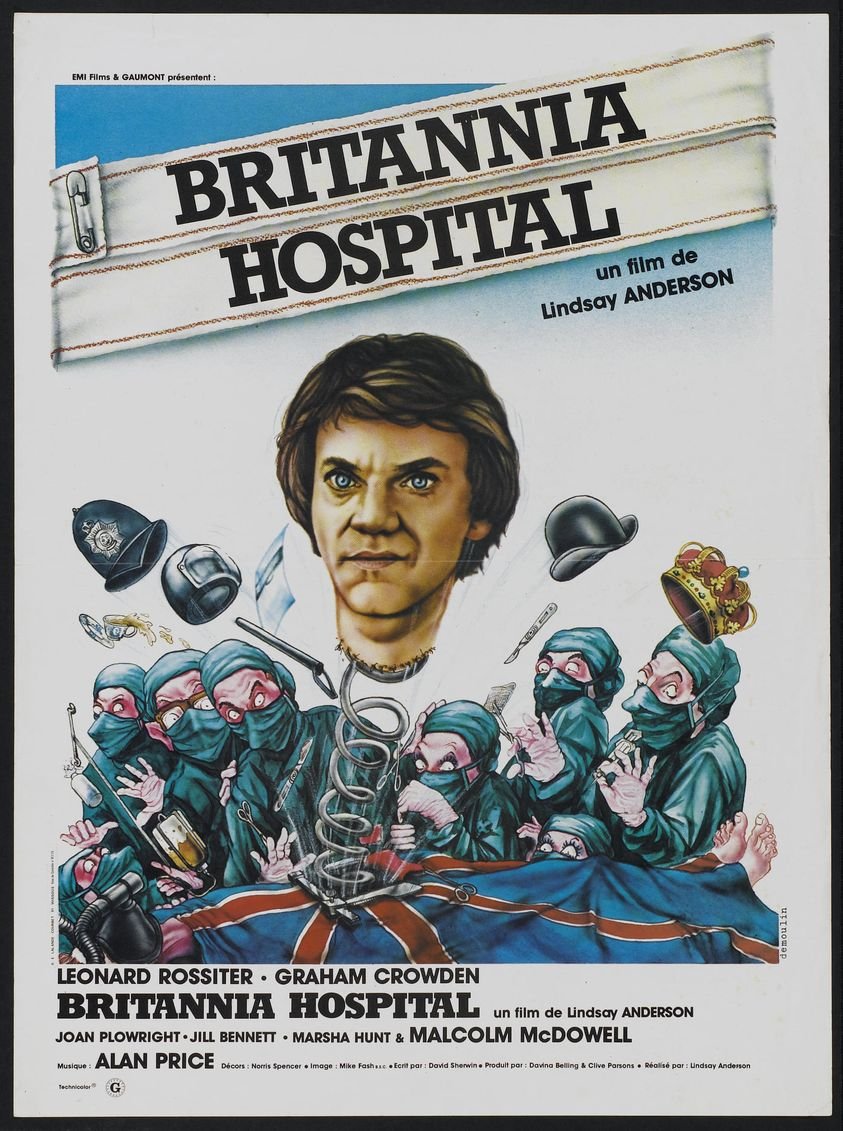

BRITANNIA HOSPITAL is the weakest entry in Lindsay Anderson's loose trilogy that includes IF… (the original FIGHT CLUB) and O LUCKY MAN! (Perhaps the most underrated film of all time.) HOSPITAL is the youngest child of the trilogy, and it isn't as memorable as the other two. Having said that, it does have one of the best endings of all time. It climaxes with the unveiling of something called "The Genesis Project," a human brain wired to machinery, which recites Hamlet in an uncanny premonition of man's foray into merging with technology.

Adrian Lyne somehow got it in his head that the only way to truly adapt LOLITA was to cast a then fifteen-year-old Dominique Swain in the titular role, nude scenes and all. This purest mentality pretty much ruined his career, as he only completed one film after his controversial adaptation of the famous novel. Controversy aside, the 1997 version does have something Kubrick's adaptation lacked; it doesn't shy away from the darkness of a pathetic man trying to recapture his youth by stealing someone else's.

From its devil-may-care tone to its rebellious characters, down to its anarchist ending, THEY LIVE feels like someone's last film; it really has no fucks left to give. A film that wasn't fully appreciated at the time of release, its cultural relevance grew over time. It's a film that has been imitated in video games and TV shows and ported over to the real world in the form of ironic advertising campaigns. The bizarre movie has become a bonified cult classic, and the cult is only growing with time. This is in part because it finds a perfect visual metaphor to communicate the enduring fight between "us" and "they."

Roger Ebert once said that a great film has "three great scenes and no bad ones." THE RULES OF ATTRACTION has some bad scenes, so it isn't a great film by the Ebert edict, but it does have two great scenes. One of them involves a drug-fueled vacation recalled at breakneck speed, the effect of which was achieved by actually sending the actor on a crazy vacation with a camcorder and saying, "do it for real."

The other great scene involves a secondary character committing suicide and being awash in regret just as it's too late to turn back.

Fellini introduced people to the self-indulgent aristocracy in LA DOLCE VITA. Here is a film that blazed light on the upper echelons of society, presenting a world of excess, fame, and debauchery amongst Rome's popular culture. There is a direct correlation between what is shown on screen here and our modern world. For starters, the word Paparazzi comes from this film, inspired by a character. But it goes beyond that; the film was a window into a lifestyle only a few people were living at the time; by the time the film was released, it became the culture the middle class emulated. It's one of the most explicit examples of art influencing life. The ultimate irony is the soullessness Fellini was indicting here was embraced by the public. The people ignored his advice and instead moved one step closer to vapidness.

Paul Thomas Anderson's PHANTOM THREAD is a romantic movie that is trepidatious to celebrate a fairytale ending too early. It instead presents a true-to-life take on love, showing the challenges and modifications we make to accommodate our significant others. THREAD ends on a peculiar note, with the previously cold fashion designer eating a steady diet of hallucinogens, the magic elixir that makes him vulnerable. A thinly veiled confession from a perfectionist director about how his own desire for control has rendered him nearly impossible to deal with.

Errol Morris's THE THIN BLUE LINE has the characteristic of being a piece of media that may have saved someone's life. This documentary changed people's perceptions in a way that ultimately got its subject freed from death row.

It's still riveting as a documentary, employing never-before-seen editing techniques that demonstrate the unreliability of eyewitness testimony and showcase how fallible human memory can be.

I would be all for Denis Villeneuve's career from now on just being a series of dares seeing if he can make previously thought to be unadaptable properties. I mean, he has proven again and again he is up for the challenge. What's that? You got a politically charged Mexican border thriller released in the height of an election year, "no problem." Alien invasion story that questions the nature of time as we know it, "piece of cake." Beloved cult sci-fi franchise, known for its vagueness and nuance; "I can do it in my sleep."

How about we give him HOUSE OF LEAVES, or maybe just put three books in a blender and say, "now what are you gonna do, Denis."

And now DUNE, his crowning achievement. Look, I was twenty-five by the time I got around to watching STAR WARS, and by that time, I was already a bit cynical and world-weary, but this made me understand what seeing that for the first time must have felt like. He took the previously mysterious, overtly political world and made it as accessible as STAR WARS. Some may call that a flaw, but I was swept up by the vision on display here. Not to mention his use of special effects as a visual metaphor, fantastic stuff. Denis makes me proud to be a Canadian.

Worth seeing if only for the villain's escape plan of releasing an intoxicating odor that makes everyone in the town square fuck. There are shots in the third act of PERFUME where there's a man in the foreground and about two hundred people having an orgy in the background. One of those flawed films that still must be seen to be believed.

The neglected next film from the guys who made AIRPLANE! A comedy comprised almost entirely of sight gags, TOP SECRET! is a dumb movie that is even more charming when you sit back and think about how much time and effort went into achieving these supremely silly jokes.

One of those films that shows the passage of time in a totally unique way, where history is happening in the background as our characters go from the plague to Richard Donner's SUPERMAN. You get the sense critics at the time were unfair to this film, eager to sink their teeth into hunks of the day Pitt and Cruise. INTERVIEW WITH A VAMPIRE also has a great mid-section; the stuff focused on Kirsten Dunst is still shocking even by today's standards.

Pitched somewhere between ARRESTED DEVELOPMENT and Shakespeare, SUCCESSION is awe-inspiring for many reasons. What sticks out to me are the pitfalls it avoids. Often shows that glimpse into lifestyles of the rich and famous fall into one of two traps. They either buy the bullshit these elites are selling and ask the audience to put these people on a pedestal, or they do the inverse, and the wealthy are painted as mustache-twirling villains, straw men pitted against noblemen proletariats in lopsided, unrealistic moral battles.

SUCCESSION does neither and instead finds pathos in these characters. This is the best kind of drama; it's not punching up or down but inviting you to watch a captivating family fight, with characters as conflicted and confused as Lear or Hamlet. Exquisite, once-in-a-decade television.

I used to consider SOUTHLAND TALES a guilty pleasure, but now, I think of it more of a cautionary tale. What is undeniable is that some of the ideas on display here are way ahead of their time; what Edward Snowden leaked about the NSA was sensationalized here in 2008, close to a decade before it made headline news.

One thing is for sure: no director committed career suicide with as much confidence as Richard Kelley did when crafting SOUTHLAND TALES.

There is no adversary in THE ACCIDENTAL TOURIST other than grief. It centers on a couple who stay together to honor the memory of their murdered son. They wallow in a loveless marriage until a dog trainer enters the picture and captures the heart of the grieving father and helps him understand what it feels like to be alive again. This often-overlooked film will speak to anyone who has wrestled with depression.

There are so many things DOCTOR SLEEP does effortlessly. First and foremost, the task of creating a sequel to THE SHINING comes with a lot of pressure, but Mike Flanagan manages to nail the eerie tone of Steven King's long-awaited follow-up book while also staying true to Kubrick's film version.

The film does a phenomenal job of handling heady concepts like telepathy and astral projection. Here is a story where people are often physically in one location and projecting their conciseness to another place across the globe. This is the kind of thing that could quickly get confusing in less skilled hands, but the film is so well crafted that you are never confused about where people are. It takes the notion of "shining" and expands on it, making you understand what having this psychic gift would actually feel like.

The most subversive thing about JOKER is that the bleak tale's first actual gag focuses on a little person who can't reach a door handle. The uncomfortable laughter this scene might elicit won't be far off from Arthur Fleck chuckling at all the wrong beats in the comedy club. Watching the movie may remind you that its director started his career with a documentary on GG Allin. That same punk rock sensibility is woven into the DNA of this film. It's no wonder it was controversial; JOKER was a provocation designed to get a reaction.

An exposé on the games married people play with each other, Ingmar Bergman's SCENES FROM A MARRIAGE is at once romantic and devastating, sweet and brutal. It shows the thin line between love and hate and how agonizingly similar those two emotions are. It's a 282 minute deep dive into the terrible things we do in the name of love.

If you ever want a hint of how uncomfortable humanity is at any place other than the top of the food chain, pop in FANTASTIC PLANET. The animated film places humans at the hands of their much bigger and bluer oppressors. The feeling of being something's plaything is unnatural and will give you a new outlook on our place in the world. The film portrays a sense of powerlessness that is replicated in Spielberg's WAR OF THE WORLDS.

Amongst the most provocative films ever made, WEEKEND follows a bourgeois couple into the woods where they are indoctrinated by a group of hippie revolutionaries who dabble in some light cannibalism. It's an overtly political film that doesn't hide its aims to brainwash the audience with its extremist philosophy.

Although I'm pretty sure the Coen's rejected this interpretation, I've always loved Roger Ebert's take on BARTON FINK. He read it as a takedown of the intellectuals employed as writers in the early days of Hollywood. These guys were praised for having gigantic personalities and strong opinions about art. Still, they failed to foresee the rise of fascism because they were too busy gazing at their navels.

PATHS OF GLORY shows the disparity between those who make the rules and those who must follow them. The way the state deals with the defiant soldiers seems so official, but all this pomp can't mask what is, in its essence, a barbarous act. This film marks Kubrick's first instance of thumbing his nose at authority, a rebellious streak that would only grow throughout his career.

A cutting and sharp Hollywood satire that showcases the ruthlessness of the industry. ALL ABOUT EVE birthed the trope of the two-faced actress, all smiles in public as roses fall at her feet, but plotting behind the scenes. She steps over bodies to grab the ladder's rungs. It's a story about the cyclical nature of backstabbing, showcasing how those who screw others over are doomed to live in fear that the same fate will befall them, always looking over their shoulder to see who is vying for the crown.

Sometimes being too early will get you penalized. Birthing the voyeuristic slasher genre two decades before it became fashionable would have disastrous results for director Michael Powell, and PEEPING TOM finished his career. Nowadays, people fall asleep to Netflix specials on serial killers and watch Freddy and Jason movies as comfort food. PEEPING TOM is tame by today's standards, and its portrayal of a man with a movie camera is surprisingly critical of the destructive male gaze.

The criminally underrated THIRST is a remake of THE POSTMAN ALWAYS RINGS TWICE, but with vampires. The love affair between two characters with an insatiable taste for blood builds to a tragic and slapstick conclusion as the two vampires try to avoid the impending rising sun with only a tiny car to keep them safe.

As a comedy, all the laughs in THE FIREMEN'S BALL come from the leaders' best intentions. They plan for a delightful evening, but all of their designs fail to predict human behavior, which is often erratic. Although Miloš Forman insisted THE FIREMEN'S BALL was only meant to be about what its name implies, the film's legacy will remember it as a satire that exposes the ineptitude of communism.

For all its transgressions, TITANE ultimately reveals itself to be about parental love. It shows how children who feel they are a burden lash out become violent and confused. Then it contrasts that by introducing a parental love that is all-encompassing and grateful. The film depicts how this kind of love can transform even the blackest of souls.

This message will come across crystal clear if you look past the heroine murdering a whole dorm of college students, getting railed hard by a flame-painted car, and lactating motor oil. On the other side of all this madness is a tender film just waiting to be embraced.

I have a fun game I play in my head when I watch CASINO; I try and figure out how they achieved every shot on a technical level. Try it yourself, and you'll soon find yourself bewildered. The wizardry on display here is genuinely impossible to keep up with, and soon you'll find yourself at a loss for figuring out how the sausage was made and swept up in the story.

Luis Buñuel's BELLE DE JOUR is about a well-to-do woman who spends her afternoons working as a high-class prostitute. It is one of the first films to depict women as perverts, a concept you sense hadn't occurred to the vast majority of men at this point in history. Not Buñuel, who spent his career chronicling all sorts of perversions.

The thing ANNIHILATION gets about aliens invading earth is how helpless humankind would be to a truly superior race. Instead of portraying our conquest as being achieved through brawn or bombs, Alex Garland imagines this incursion delivered through the tender embrace of a long-lost loved one.

After all, the most efficient way of defeating another species would be to fool them into thinking they've actually won.

A parody ahead of its time, WALK HARD: THE DEWEY COX STORY, was released in 2007, well before the tropes of the musical biopic were ingrained in our collective conscience. To this day, the clichés this lewd film sends up are employed without irony by storytellers trying (and failing) to breathe new life into the narrow confines of this dull genre. Be warned; WALK HARD will ruin your ability to take any earnest film about musicians seriously.

The notoriously unsentimental Coen Brothers would probably cringe at the suggestion, but INSIDE LLEWYN DAVIS may secretly be about their lifelong partnership.

Think about it; the film centers on the titular character who has recently released his first solo album after his longtime partner committed suicide. The album isn’t selling, and Llewyn finds himself drifting into obscurity without the support of his former collaborator. The bleak tale may be the Coen’s unconventional way of saying, “I can’t do it without you.”

MIDNIGHT MASS has its cake and eats it too, and I mean that as a compliment. The Netflix show feels like the screed of an angsty teen who wants to tear down the institution of religion blended with the maturity of someone who has lived long enough to see the many benefits of it. It's as excessive as a zombie film and as deft as a Bergman film. It wants to convey the message that God doesn't have a plan for everyone, yet, upon scrutiny, if you analyze the events and how they unfold, you see how everyone on Crockett Island played their part to bring down the demon. It knows enough about mass appeal entertainment to give you the blood and guts you want from a horror film and yet shows surprising restraint throughout. Its ending could be interpreted as the purifying floods of the Old Testament or the rapture of Evangelicalism. And to top it all off, it dares to cut to black on a tragedy asks you to see it as a miracle.

It's a modern-day classic and the best thing Mike Flanagan has done, even if I suspect it was first conceived of by getting really high and staring at the front cover of Meat Loaf's Bat out of Hell for too long.

All legal proceedings start with one person's word against another; sometimes, the law pits influential people against the meek and vulnerable. 12 ANGRY MEN is a celebration of stubbornness, dogged determination, and reasonable doubt. Slowly but surely, it chronicles the sequestered men's lingering uncertainties until they all topple like dominoes. It's a film that worships at the altar of logic and celebrates justice being blind to status.

Tarantino said something spot on about JACKIE BROWN. He said if he stayed on the same career trajectory, JACKIE BROWN would have been the kind of film he would have made in his late 70's; he just happened to get it out of his system when he was 40. He credits this "time leap" with freeing him up to be more audacious in his choices moving forward.

Sometimes you hear what inspired a film, and you understand exactly how the concept coalesced. Wes Craven read a series of articles about refugees dying in their sleep from traumatizing nightmares after fleeing to America from the Vietnam war. You can almost see the wheels in Craven's head turn as he thinks, "a nightmare that kills you."

GROUNDHOG DAY is a film no one can accuse of blowing its premise. It goes dark, it has wish fulfillment, it has hijinks. Harold Ramis milks every possible outcome within the parameters of the stuck in the same day idea. Not only does it exhaust anything you could ever want from a concept like this, but then it does the impossible, and the repetitive structure becomes a metaphor about living a life of service, even if it's the same shit different day.

Who would have thought that Louis Malle was birthing an entire subgenre of porn when he made MURMUR OF THE HEART in 1971? Malle referred to the incestuous story as semi-autobiographical, a fact that probably made people take pause before ever affectionately calling Malle a "mother fucker" ever again. But in all sincerity, the film finds tenderness in the uncomfortable situation and deserves praise for tackling a taboo subject matter with grace.

CLOSE-UP demonstrates how a love of film can transform into an unhealthy obsession. The movie about a cinephile who impersonates his favorite director and gets caught up in a fraud case shows great sympathy for its confused protagonist. The film understands that all film lovers begin as impersonators and imposters, pretending to be their hero's until they have sourced enough inspiration to fool people into thinking they are original.

The most amusing thing about ERASERHEAD is how it was received as some indecipherable surrealist artifact whose hidden meaning was impossible to decipher. It's weird because the film is practically screaming: "I'm terrified of becoming a father" from the top of its lungs as its only real message.

It's clear why Steven Soderbergh took a short-lived break from moviemaking after CHE failed to set the box office on fire; it's arguably his best film, and it performed as if it was one of his worst. It was a two-part, four-hour behemoth that felt like something that would have only been green-lit twenty years earlier.

The first part shows the triumphant revolutionary takeover of Cuba, and the second part contrasts that with the failed takeover of Bolivia. To me, the film has always been about the folly of trying to recapture lightning in a bottle; it's about how doing the same thing twice will inevitably lead to defeat. A fitting thesis for a director who seems to reinvent himself every five years.

It almost seems as if the main character at the center of Todd Haynes's SAFE becomes allergic to things. Throughout the film, she searches for the source of her strange illness, until by the end of the film, she finds herself living in a commune where they have no possessions. The film starts with a suburban woman who ostensibly has everything and takes her on a journey to having nothing. It is only through shedding herself of all these things that she finds peace.

Hollywood is often criticized for spoon-feeding social justice causes thinly veiled as art. But when a worthy cause meets a great story, the result can be transcendent. Great art can make us agree on things we as a society are still grappling with. If done with a gentle touch, a transformative piece of art can tip the scales in our collective unconscious and define morality going forward.

Take the case of DEAD MAN WALKING, which tackles the hot button issue of the death penalty. Rather than preach, the film unflinchingly crosscuts between the brutal rape and murder the criminal at the center of the film committed with the state carrying out his execution.

In taking an approach that doesn't hide anything, the film stands firm in its message: that killing is wrong regardless of the circumstances, and even the most wretched amongst us deserve forgiveness.

THE SEVENTH CONTINENT is an early offering by Michael Haneke that proves he appeared on the scene fully developed as a director whose films always pack a punch.

The movie concerning a middle-class family that decides one day to destroy all their possessions and kill themselves is not for the faint of heart, it is brutal and unwavering in its singular aim, but it is also unforgettable and strangely emotional. The film deserves to be mentioned alongside other films that tackled our gluttonousness as we neared the turn of the century. It would make a great double feature alongside Todd Haynes's SAFE, and then you can cap off the night by sticking your head in the oven.

One of the most unapologetically conservative movies ever made by Hollywood, ROLLING THUNDER, plays like a fever dream revenge fantasy. The man who dutifully served his country in Vietnam returns home to discover that he doesn't recognize America anymore. Displaced, and trained for years to be violent, he searches for a cause worth killing for. In many ways, this is the maladjusted, problematic version of TAXI DRIVER, and I'm here for every minute of it.

It's a good thing WAG THE DOG was released before the world was inundated with conspiracy theories. You get the sense that some would confuse the jokes for truth. Nevertheless, the core idea of a seasoned film producer invited to Washington to "produce" a fictional war to distract from a Clintonesque sex scandal has some amusing moments that ring true.

To me, the film is a confession on the dark magic Hollywood uses to mesmerize the world. And how anyone who threatens to reveal how the sausage is made is expendable.

I read the script for INGLOURIOUS BASTERDS a year before it was released, and I figured the ending was a placeholder. I remember reading it, mouth agape, and thinking, "there is no way this ending makes it to the big screen!"

Flash forward to a year later, I'm invited with a few friends to a sneak preview of BASTERDS with Quentin in attendance; Weinstein was there too, watching over everything like the Fuhrer. By the time that third act rolled around, I was on the floor laughing; I could not believe he got away with such a gonzo conclusion.

Tarantino said something interesting after making JACKIE BROWN; he said he had an obligation to make insane movies, the kinds of films only he could get away with making. INGLOURIOUS BASTERDS is him fulfilling that solemn obligation.

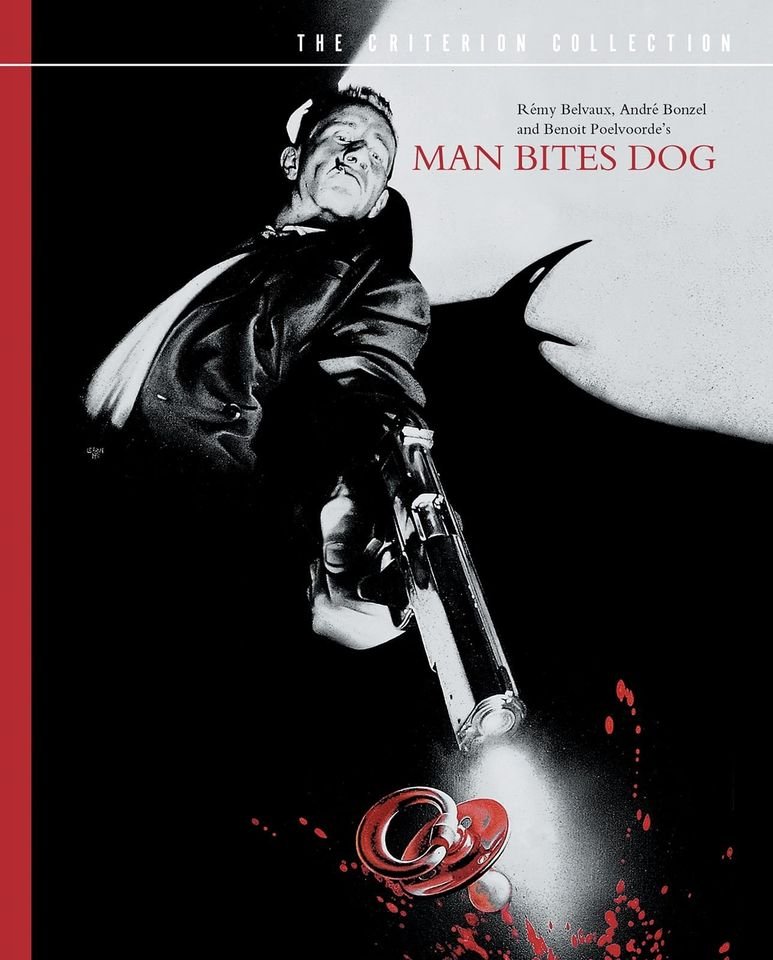

Has any poster more adequately prepared you for what you are in store for better than the MAN BITES DOG one you see here?

The story of a documentary camera crew who is seduced to follow along with a serial killer and eventually partake in his crimes is one of the darkest comedies of all time, finding gallows humor in things that just aren't supposed to be funny. This mockumentary has a bunch of copycats, but nothing compares to this dive into total madness.

Decades from now, if anyone is curious enough to ask, "what was living through the pandemic like?" we can pop on BO BURNHAM'S INSIDE to explain it to them.

Acting as a time capsule, this is a touching and hilarious portrait of 2020, the toll it took on our collective mental health, and one man trying his best to make us laugh through it.

My favorite thing about WALL-E is that Steve Jobs pitched it to Pixar as "a love story between a Mac and a PC." That always struck me as an uncharacteristically tender thing for the apparently insensitive man to stay. It's kind of sweet that Jobs felt like making a love letter to his business rival in the twilight of his life.

FARGO has a fascinating structure. It has scene after scene of awful people doing awful things to each other for an hour and a half. Then, it finally shows you a couple being nice to one another in the last two minutes.

The juxtaposition is jarring; after being inundated with the worst features of humanity, you cannot help but be moved as a wife congratulates her husband on getting a modest second place in his stamp competition. It is overwhelming because of what came before. This beautiful moment acts as the blindingly warm light at the end of a very dark and twisted tunnel.

Pedro Almodóvar one-ups Eric Cartman in SCOTT TENORMAN MUST DIE for the most ruthless revenge with THE SKIN I LIVE IN.

You may think you've seen all the revenge plots there are, but you don't know the depths of degradation until you've seen a man use plastic surgery to transform another man into his dead wife.

Shot in Mexico for a mere $750,000, THE HOLY MOUNTAIN looks like it cost at least 30x more than that.

The centerpiece of the film is an intro to seven characters who each represent an industry. Here, Jodorowsky sends up weapons makers, cosmetics, art dealers, and organized religion. He ridicules these institutions with what seems like enough material for ten films.

Long before FIGHT CLUB questioned our dependence on material things, Jodorowsky encouraged you to burn your money, embark on a spiritual quest, and find a cause worth living for.

THE NIGHT OF THE HUNTER is a child's nightmare.

It takes the things kids look to for protection and slowly strips them away till all that remains is a bad man who pursues them through the countryside. There, the children find a protector who resembles the woman in "American Gothic," but instead of a pitchfork, she packs a shotgun. This badass granny fearlessly faces off with the devil and becomes the savior of these lost children.

The sole film from director Charles Laughton has been parodied and copied so many times that people forget where the trope originated. Laughton uses the extreme wides to create a sense of helplessness, where you can see precisely where the threat is coming from, but you are paralyzed to do anything as it walks straight to you, like a slow-moving death.

If you want an indicator of how great Krzysztof's Kieslowski's RED is, Quentin Tarantino even acknowledged that it should have won the Palme d'Or instead of PULP FICTION that year.

The people depicted here are flesh and blood, but the film feels like a dialogue between angels and God. It's a conversation where the answers to life's mysteries are resolved, the synchronicities that seem random are laid bare, everything seems linked by miles of telephone wires that stretch underground and connect us all.

The film ends in a sequence where seven people miraculously survive a cruise wreck. Seeing the film isolate who those people are might be the most daring religious message ever put to film.

THE LOVE WITCH is even more impressive when you realize how many hats writer and director Anna Biller had to wear to bring her technicolor vision to the big screen. The film channels Alfred Hitchcock and Douglas Sirk to such a degree that it feels like an overlooked gem of the era. It's so draped in the aesthetics of the '50s that you might not realize just how subversive it gets. By the time the film shows you Satanic rituals in exacting detail, you may get the hint of just how provocative Biller is being here.

The film works as a feminist empowerment statement just as much as it works as a whimsical exploration of borderline personality disorder.

The beautiful contradiction that makes FRANCES HA so pleasant is that it features a character who insists she is "undateable" and "unlovable," but the film is directed by someone who is clearly head over heels in love with her.

This character study has the score and tone of a romantic comedy, but it couldn't be further from that. This is a love letter to the weirdos in life, the people who take longer to develop. Rather than pinning a happy ending on this odd duck finding love, it instead expresses enormous gratitude for the friends we meet along the way, who are patient enough to understand we are still under construction.

FRANCES HA is a great film to replace MANHATTAN as the classic black-and-white New York looking-for-love story, as the Allen film is almost unwatchable nowadays.

FILTH is the movie equivalent of being taken out for a night of drinking with a group of unruly guys who keep making you the butt of the joke as pat you on the back and reassure that they're just taking the piss out of you. It is a raucous movie that never slows down long enough for you to pinpoint whether it's serious or a dark and twisted joke.

That devil may care tone carries through all the way to the last scene, where it slows down and becomes heartfelt, only to pull the rug out from under you at breakneck speed for one last jab at the ribs.

Bob Fosse’s ALL THAT JAZZ vacillates between boozy confession and razzle-dazzle with wanton abandon. It is a movie made by someone who can’t help but be a showman even as he explores the subject of death.

It remains one of the only films to genuinely show the toll show business can take on an individual. This cautionary tale from a man who used and abused women, drugs, and alcohol and skated by on his charm has the power to make you admire this extremely flawed person even as he dances his way to oblivion.

If the internet were a thing when KISS ME DEADLY was released back in 1955, it would be the subject of countless videos on YouTube that promise “KISS ME DEADY: Ending Explained.”

Elements of this hard-boiled noir were lifted in films like LOST HIGHWAY and PULP FICTION. It remains a better-than-average film noir that builds to an ending that will forever be ingrained in the minds of anyone who has seen it.

PALINDROMES is technically a continuation of Todd Solondz's second feature, WELCOME TO THE DOLLHOUSE, but if that eludes you, it's probably because he employs a gimmick where a different actress plays the main character from one scene to the next.

This film touches on such hot-button subjects as abortion, 9/11, and radical Christian fundamentalism. In the film's best scene, which seems directed at Solondz's harsh critics, one character insists, "I'm not a pedophile." To which another wryly responds, "I believe you, pedophiles love children."

Many people love to point at films and say, "that would never be made in today's climate," but it's a miracle any Solondz film was ever made. His movies are just as shocking as they were when they first assaulted viewers.

REAL LIFE was made as a spoof on a television program called AN AMERICAN FAMILY, but it also ended up prophesying many reality television troupes.

The directorial debut from Albert Brooks foretold how shows like BIG BROTHER would hide cameras as well as how meddling reality tv producers would coerce real-life talent into doing things entirely out of character. Brooks divined all of this in 1979 before the phrase "Reality TV" was even a thing.

In FIGHT CLUB, the men lament, "why do guys like you and I know what a duvet is?" Compare that to GONE GIRL, where yuppies Nick and Amy buy each other the same type of luxury 2,000 thread count bed sheets.

There may be a thematic connection in the bedcovers of the two David Fincher films. Whereas the former film envisioned men living without the creature comforts of life, scared of womanly influence, GONE GIRL shows women conquering men. But instead of winning the battle through force or fists, they lure men into comfy nests and strike with precision timing. If FIGHT CLUB was about guys worrying about losing their balls, GONE GIRL is about that fear manifested: it's one man's journey to being thoroughly neutered.

None of this even touches how fucking funny it is. Since Nick is set up to be such a tangle of rash masculinity, you are invited to feel good about giggling as he is firmly put in his place.

Ben Affleck is particularly remarkable in an often thankless kind of straight-man role. The people nominated for best actor or actress at any given Oscars are usually the people who cry the hardest, who shake and tremble with wild histrionics. Here Affleck is tasked with playing someone terrible at expressing how he feels. He is so bad at conveying his inner emotions that the entire plot turns when he shows his humanity and wins back the affection of his psychotic companion.

One of the first films to place you inside the head of a character and make you feel their anxiety. AFTER HOURS walked so UNCUT GEMS could run.

This film is about a guy having an awful night that captures that feeling of a minor problem snowballing into a disaster, a molehill growing into a mountain. Scorsese's indie plays like Kafka's THE TRIAL, but instead of some faceless authority torturing our hero, it's the ruthless SoHo district of New York in the mid-eighties.

Directly after skewering Hollywood with SUNSET BOULEVARD, Billy Wilder set his sights on the media.